International bitcoin “miners” are reaping rewards from China’s effective ban on the energy-intensive practice, generating ever higher profits by filling a vacuum left by former Chinese rivals in creating digital tokens.

China’s largest bitcoin-producing provinces launched a clampdown on computer-powered bitcoin mining in June, part of a broader attempt to cut down on carbon emissions and a push against private cryptocurrencies as the country works on its own officially-backed digital coin.

The country had been the world’s biggest producer of bitcoins, accounting for half of the global output. Miners elsewhere say cooling production there has opened up the market to other competitors.

“Think of average daily global bitcoin production as the pie. The size of the pie stayed the same, and each existing miner was able to help themselves to a much bigger piece,” said Shane Downey, chief financial officer of Hut 8 Mining, a Toronto-based listed company.

Bitcoin miners create new coins by using powerful computers to solve mathematical puzzles. The number of coins that can be produced each day is fixed, so with fewer rivals, it is easier and cheaper to make new coins.

The improving economics has meant that entrepreneurs are now launching new mining operations in countries around the world.

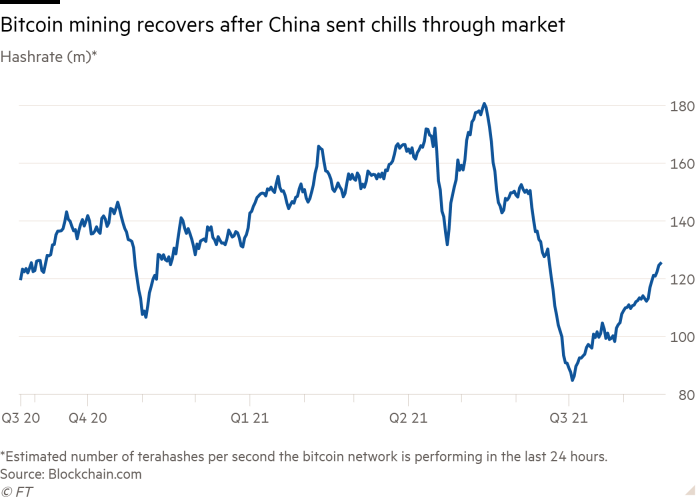

The overall computer power dedicated to bitcoin mining globally initially halved in the aftermath of China’s move, but it currently stands about 30 per cent lower than in May, according to data website Blockchain.com.

The profitability of bitcoin miners depends on the prevailing market price of the coins, the cost and amount of electricity required to run the servers and the rate at which new units can be mined. Bitcoin’s rise on Monday back to $50,000 from summer lows below $30,000 could add a further incentive to miners.

“It’s like we’ve doubled the number of machines we have,” said Fiorenzo Manganiello, the founder of private equity company Lian Group, which owns one of the largest renewable bitcoin mining farms in Europe.

Hut 8 Mining has been one of the companies benefiting. The company notched up a 241 per cent year on year boom in mining revenues in the second quarter, raking in C$31.4m ($25m), with its chief executive noting that June and July proved to be bumper months as a result of China’s move. Mining profits registered C$19.3m over the period, from C$697,000 in the same period last year.

“Following China’s ban on domestic miners, global [production] fell by approximately 40 to 50 per cent, and at Hut 8, we started mining approximately 40 to 50 per cent more bitcoin, with no directly attributable cost increase,” Hut 8’s Downey said.

UK-based mining company Argo Blockchain also reported a 180 per cent increase in revenues in the first half of 2021, citing a change in global mining conditions that allowed it to produce more digital coins without increasing the number of machines it uses. Pre-tax profits soared to £10.7m, compared with £523,074 in the first half of 2020.

Sam Doctor, chief of strategy at US digital asset specialist BitOoda, estimated it would take about 18 months for capacity to return to pre-ban levels. Replacing the lost capacity will take time because it involves upgrading power infrastructure and building new facilities.

Miners from China have tried to migrate to neighbouring countries such as Mongolia and Kazakhstan, but many are unable to transport the equipment across borders. There are also concerns about the stance authorities will take about bitcoin mining in these new hubs.

Bitcoin mining has a severe environmental impact. It accounts for 0.4 per cent of the world’s energy consumption and it uses more electricity annually than Finland or Belgium, according to the Cambridge Bitcoin Electricity Consumption Index. Miners in China had a particularly large effect due to their reliance on coal-powered energy.

“As things stand today, we believe cryptocurrencies have a long way to go to satisfy ESG criteria,” said analysts at French asset manager Candriam in a recent report, referring to investment standards pertaining to environmental, social and governance issues.

Outside of China, mining activity is gravitating towards places with abundant sources of renewable energy, such as Norway and Canada. But as demand exploded, specialist site operators have found it hard to build new facilities rapidly enough.

“It will take about a year or more for mining capacity to recover. There is a lot of new mining equipment being sent to the US and Canada instead of China, but data centre capacity is a bottleneck,” said Kjetil Hove Pettersen, chief executive of Norwegian miner and datacentre operator KryptoVault.

In the US, Texas has been one of the key beneficiaries of the new landscape, while specialist sites in Norway and other European countries are buckling under demand.

“We have people calling us and begging us to accept their machines. Some have offered 50 per cent of their future profits if we give them space in our data centres,” Manganiello added.

The price and quality of computers required for mining new units has also declined. Before China’s crackdown, miners had to pay ever increasing prices for their computers as they searched for more efficient ways to acquire bitcoins. Due to the glut of servers now collecting dust in China, the price of computers has collapsed and barriers to making money have become lower.

“Right now, the profitability of bitcoin mining is so high that even the oldest, least efficient machine can be profitable,” said KryptoVault’s Hove Pettersen.